Have you ever read a book about a place you know well and thought No, that’s not it at all!

What are the challenges to an incomer writing well about a place they weren’t born and raised in? Is the perspective of a native inherently more valid? Do the relative merits complement each other or clash?

Sun 25th April 4pm English

Debut Authors: Writing Wales | Sponsored by Mari Thomas Jewellery

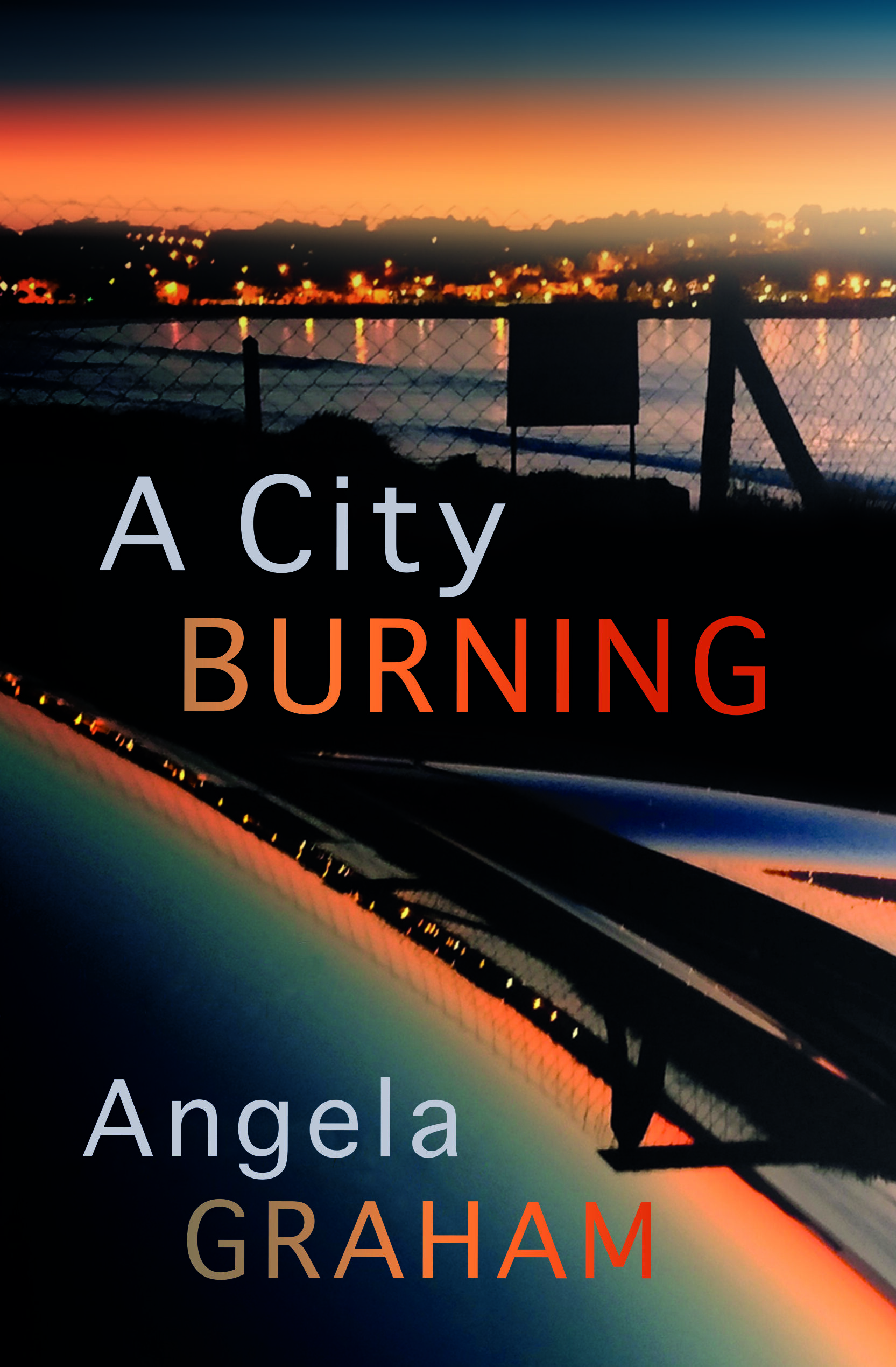

Join debut authors, Welsh woman, Angela Johnson and Belfast-born Angela Graham, as they discuss their experiences of putting Wales on the page in their new books, Arianwen, a warm and witty novel set in West Wales, and A City Burning, a confident collection of stories set in Wales, Ireland and Italy.

Arianwen has been described as ‘brilliantly evocative’ with ‘lilting Welsh rhythms and poetic imagery’; A City Burning was named ‘ a book of the year’ by Nation Cymru in 2020, and described as ‘wonderful’ by the Irish Examiner.

I’d like to think ahead to my session alongside Angela Johnson, author of Arianwen.

I was born and raised in Belfast. I’ve had to ‘learn’ Wales. I’ve written stories about Welsh people and places (some partly in Welsh) in my collection, A City Burning. Does my perception differ from that of a native? Yes, I believe it does. Do I get Wales and the Welsh ‘right’? Right by whose criteria?

I’ve certainly seen some very poor writing about Wales from a few authors who are not from the place. The worst examples portray the Welsh as amiable softies, charmingly somewhat behind the times, or as exotic, brooding Celts, ‘up to no good in the back lanes’ as Harri Webb puts it is his sharp poem, Synopsis of the Great Welsh Novel.

I first visited Wales, or at least, the Rhondda and Porthcawl, in the scorching summer of 1976. I came to live here in 1981, newly married to my Welsh husband. He’s from the Rhondda, a Welsh-speaker. In getting to know him I had already understood that being a Welsh-speaker is not an uncomplicated thing and neither is being Welsh. What looks homogenous to an uninitiated outsider is not so to the native.

The Welsh read themselves – no; I should, of course, say read each other − according to a subtly calibrated schema of place, family linkage, language, class and religion within an intricate web of political allegiance. Doesn’t every nation? Yes, I suppose so, but the Welsh often relish the task. In Northern Ireland, where I’m from, the same thing is done but wearily and warily.

I began to learn Welsh as soon as I could. I did this because I came from a place where even the nuance of accent said something about the speaker’s identity and affected the disposition of people in a conversation. So, I reasoned, the role of a language must be even more important. I wanted to at least get to the stage with Welsh where no one would be obliged to turn to English to talk with me. I’m still learning but I’ve had a long career in television and cinema production, about 50% of which has been in Welsh.

I was lucky to make many programmes about Welsh history. I was a member for 8 years of Teliesyn, the wonderful tv and film production co-operative. I worked as a producer with two of its staff who have exceptional track records in the area of history on television: the late Prof Gwyn Alf Williams and the director, Colin Thomas. I was Development Producer on the landmark BBC series The Story of Wales, presented by Huw Edwards.

I’ve been privileged, through my work, to have travelled the country extensively, encountering people from many walks of life. I have three Welsh children. And of course, I’ve been immersed in the Welsh family I married into.

How one sees a country and its culture and people must depend on which parts of it one gets to know and also on the lens through which one carries out that scrutiny. I could not, at first, help looking at Wales from a perspective that had been honed in a place that was convulsed by violence, patrolled by police and army, openly disturbed. Wales seemed peaceful by comparison. But I came to realise that beneath its surface there was plenty of fission going on.

Over the years I have asked a lot of questions of the Welsh. Things they take for granted don’t seem so obvious to me.

Perhaps my Wales-set stories hold up a particular kind of mirror to the place and its inhabitants. Will you recognise yourself there, Welsh or not?

https://llandeilolitfest.org/festival-books-for-sale/