Recently I had a poem about gorse on the Pendemic.ie site which describes itself as, ‘Not a literary magazine for ordinary times, but journaling the extraordinary.’ in these COVID-19 times. My poem describes the gorse that flowers copiously in Ireland in Spring.

I had many responses on Twitter, sharing a love of gorse and of poetry inspired by it, old and new. I’d like to bring some of them together here to share that pleasure further, as a simple record. This is a mere fraction of the gorse-related poetry one might find.

There was also an interesting exchange about the other names of gorse: whin and furze. (Of which more in a later post).

Gorse has been attracting attention in Ireland for a long time. An excellent example is the ninth-century poem in Irish about a blackbird perched on a gorse bush.

On the website of the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s University Belfast, the late Ciaran Carson explains why he chose the blackbird as the Centre’s logo – in doing so he gives this Irish poem, ‘The Blackbird of Belfast Lough’ alongside versions by Seamus Heaney and himself. A real treat.

He writes: ‘ the(Irish) poem suggested a fitting emblem for the Centre. Hence our logo, the elegantly spiky wood engraving of a blackbird singing from a ‘whin’, or gorse bush, by the artist Jeffrey Morgan.’ ‘The Yellow Nib’ is a poetry journal produced in association with the Centre. The Blackbird

Here is John Erskine’s beautiful Ulster-Scots paraphrase of the same poem from the Irish. (reproduced with his permission) See: Ullans

Tha Merle bi Lagan’s Loch

Tha bricht wee burd

haes wheeple’t furth:

an airra frae

a yella neb;

blythe, skails its sang

owre Lagan’s Loch;

a merle, atap

a yella whun.

Among Dr Frank Ferguson’s suggestions is John Hewitt’s response to the original poem (reproduced with permission from the John Hewitt estate) which grapples with the difficulties of translation:

Gloss: on the difficulties of translation.

Across Loch Laig

the yellow-billed blackbird

whistles from the blossomed whin.

Not, as you might expect,

a Japanese poem, although

it has the seventeen

syllables of the haiku.

Ninth-century Irish, in fact,

from a handbook on metrics,

the first written reference

to my native place.

In forty years of verse

I have not inched much further.

I may have matched the images;

but the intricate word-play

of the original—assonance

rime, alliteration—

is beyond my grasp.

To begin with, I should have to substitute

golden for yellow

and gorse for whin,

this last is the word we use

on both sides of Belfast Loch.

Mark Thompson also shared two poems, ‘County Down, by R. Lloyd Praeger. Here are a few lines:

“The comely Ards, the pleasant Ards,

Dear land of little hills…

Of darkling bogs, and long-dry moss

Where the whin’s gold glory burns;’

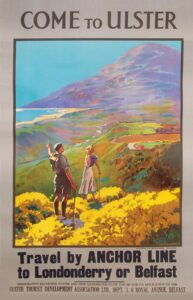

and one by Ernest Milligan from his “Up Bye Ballads” called “The Braw Whin Bush” ‘in which Milligan advocates that all Ulstermen should wear a sprig of gorse in their lapels .’

Here’s a verse:

We Ulster men look dourly,

Speak sharp at times an’ sourly,

Yet if you could but know us right we’re kind enough within.

An’ you’ll always find the gold in

Our very hearts enfoldin’,

Though we’re gruff at times, an’ scoldin’, rough an’ jagged as the whin.

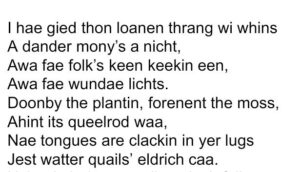

Two contemporary poets now. Daniel Seawright (@SeawrightDaniel) says of his Ulster Scots contribution: ‘Here’s a loanen full of whins from the opening of a (very) braid narrative verse ghost story:

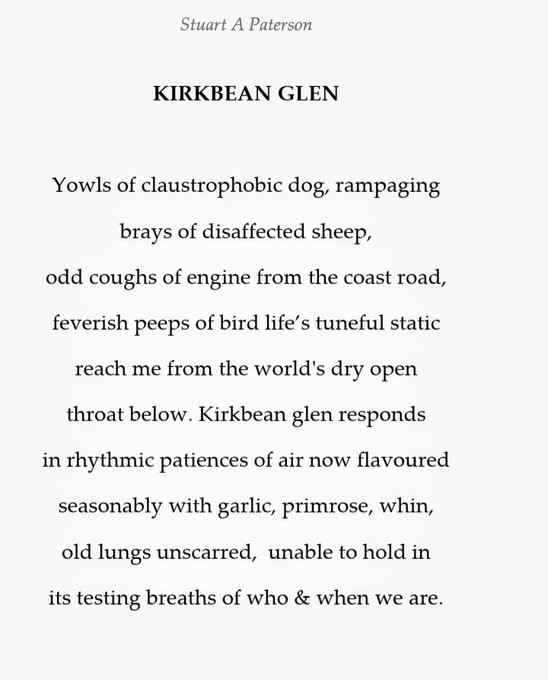

and Scots poet, Stuart A. Paterson

My thanks also to Dr Carol Baraniuk for advice and help..