The 500th anniversary this year of the Protestant Reformation is marked in Berlin by two key exhibitions. In September I saw both the Luther Bilder / Luther Pictures at the Gemaldegalerie and The Luther Effect – 500 Years of Protestantism in the World at the Gropius Bau.

From the Bilder exhibition this is my favourite detail: the beaked, cheeky figure – human or not? – raving it up among a group of Catholic clergy in a pro-Luther parody…

… a coloured woodcut by Lucas Cranach the Younger and Pancratius Kempff.

It’s unambiguously entitled...

This depiction of the pious Protestants on the left and the venal Catholics on the right is a graphic insight into how things looked to the Protestants of 1546.

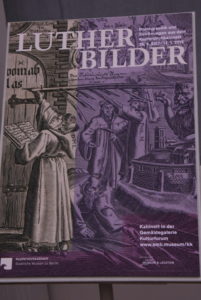

This Bilder exhibition is a series of images of Luther covering 100 years from his major challenge to the Catholic Church in 1517.

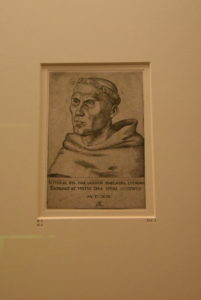

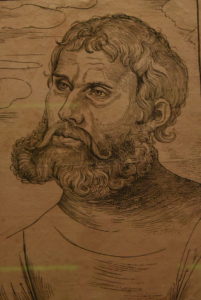

To be able to walk, image by image, from the earliest, in which he is depicted as the lean, young Augustinian monk that he was…

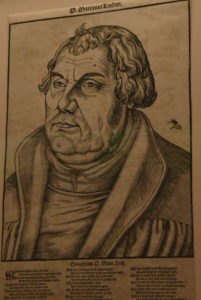

… to the comfortably jowled pater familias that he became…

… is to experience in a special way the sense of one man’s journey through time and life – and this man had first-rate artists, especially Lucas Cranach the Elder and Younger, to document his progress and printing to disseminate his image along with his ideas.

I also particularly liked this portrayal by Lucas Cranach the Elder of Luther as an aristocrat, done to prove he was still alive after the Elector Frederick the Wise had him abducted and held in Wartburg for his own safety for a year: a reminder of how turbulent and unpredictable life must have been for the protagonists of the time.

Images from the Martin-Gropius-Bau exhibition The Luther Effect can be found here. This both displays key artefacts and images of the Reformation period and documents the impact on several countries: USA, South Korea, Sweden and Tanzania. The exhibits which aim to portray the ‘Luther Effect’ in the selected countries are fascinating and include contemporary interviews.

In the world map on display Wales is invisible. It’s England, apparently, which wipes out any sense of the particular impact of the Reformation in Wales.

It is wonderful that materials are brought together from the earliest days of the Reformation in Europe, including , for instance, The Boke of Common Praier, 1559 which I had never seen before but I found aspects of this exhibition disappointing because of the simplistic nature of some of the interpretation.

For example, the central atrium of the building is taken up by a double helix installation, Transition by Hans Peter Kuhn representing the opposing natures of Protestantism and Catholicism. One walks through this huge twisting construction whose dipping and rising sides mirror one another.

“In the vertical line, Catholicism blocks the direct access to God, while in the horizontal direction it leaves room for pardonable sins. Protestantism, on the other hand, grants the freedom to have a personal relationship with God, but no longer allows for casual sins.” (Exhibition Booklet)

While it presents the approaches, on a positive reading, as complementary, it seems to deny they have anything in common which, in my view, is a serious misrepresentation.

By polarising them in this way for presentation to people of today, as though nothing has changed since the sixteenth century, it also misrepresents the nature of Catholicism which does not block a personal relationship with God, and never did, and one has to ask what is meant by asserting that Protestantism ‘allows for casual sins’. It’s shorthand for complexities.

But I’m no expert so I’ll be reading the newly published The Making of Martin Luther by Richard Rex (Princeton University Press) which aims to ‘explain Luther’s ideas’.