Ding Doon Tha Mairch Dykes – a quotation from a collection of poems by Stephen Dornan heads up this article by me in The Irish Times of 3rd March 2021 here

In 2017 I received a SIAP Award from the Arts Council of Northern Ireland towards research for a novel set in NI. One of the most striking currents in the air was the turbulence around issues to do with language, with Ulster Scots and Irish. The Stormont Assembly collapsed partly because of apparently irreconcilable pressures around the way people speak; how they write; their cultural ‘reading’ of the land itself.

Language and land – two permanent pieces of the NI puzzle. Language embedded in land, in heart, in psyche.

I noticed also some important shifts in population presence within Northern Ireland; the move from city to country; the changing ownership of land and property; demographics impacting on communities.

From these arose a contemporary story, but it could only be told, I felt, through English, through Ulster Scots, through Irish.

I didn’t find it hard to access materials in Irish or to access advice but when it came to Ulster Scots, although I had that in my inner ear from my father’s side of the family (as I had Irish from my mother’s), it was a much tougher enterprise to gauge its contemporary use, to inflect this according to age, area and class. Some of the reasons for this are mentioned in my article.

I am enormously grateful to each person who has helped me along the way, in both Irish and Ulster Scots.

I am absolutely delighted that, in these few years, there has been an opening up in the Ulster Scots field, a writerly energy that wants to be expressed across forms and registers. Again, the article touches on this but there would be much more to say and report.

I would like to see, in Irish publishing, particularly among journals and magazines, a greater readiness to consider publishing – alongside English – Irish and Ulster Scots too. The Bangor Literary Journal published a pair of sonnets I wrote in Ulster Scots and English. The sky didn’t fall in.

I wrote a story partly in Ulster Scots for my collection A City Burning. The publisher, Wales-based Seren Books, was interested in the calibre of the work, its intelligibility, its coherence and the Ulster Scots earned its place on those terms.

There are challenges to trying to get Ulster Scots (a) written and (b) published outside specialist publications. Where is the material? Who is to judge its competence? Can Ulster Scots recover itself enough to flourish today?

These are questions appliable, in varying degrees, to any minority language or dialect.

Certainly, no one gains from setting one form of expression against another; or from over-zealous gate-keeping about standards (though these must exist or expression gets catastrophically unmoored from its roots); or – most insidious of all – who is to be allowed to write in Ulster Scots.

That last was the pressure that threatened most powerfully to hold me back. But I have finished the first draft and it has been a wonderful experience to live with the characters, and particularly the Ulster Scots speakers, seeing the world through those eyes, speaking with that tongue.

But perhaps the time has arrived when a new set of questions can be asked: Why not in Ulster Scots? Why not me? Why not now?

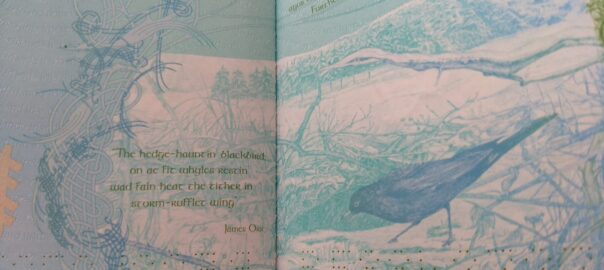

The Header illustration is a page from the passport of Éire / Ireland: Ulster Scots words, by James Orr