Prof Diana Wallace researches women’s writing, with special interests in historical fiction; Welsh writing in English and Modernism and the Gothic. She is co-director of the Centre for Gender Studies in Wales and Leader of the English Research Unit at the University of South Wales. Her review appears on the website of the Centre for the Study of Media and Culutre in Small Nations at the University of South Wales.

How can writers respond to sudden, even exponential, change? It can take a decade, as it did after the first world war or 9/11, for novels and memoirs to catch up as writers process traumatic events. And readers, time-pressed and battered by 24-hour news, may turn to genre fiction for the comfort of familiar plot lines and predictable endings. The short story, on the other hand, can turn on a sixpence to give us a snapshot of our crises in real time. Compressed, intense, often challenging, some of the most powerful examples of the form have come from writers on the so-called margins: women, immigrants, people from ‘small nations’ such as Wales and Ireland.

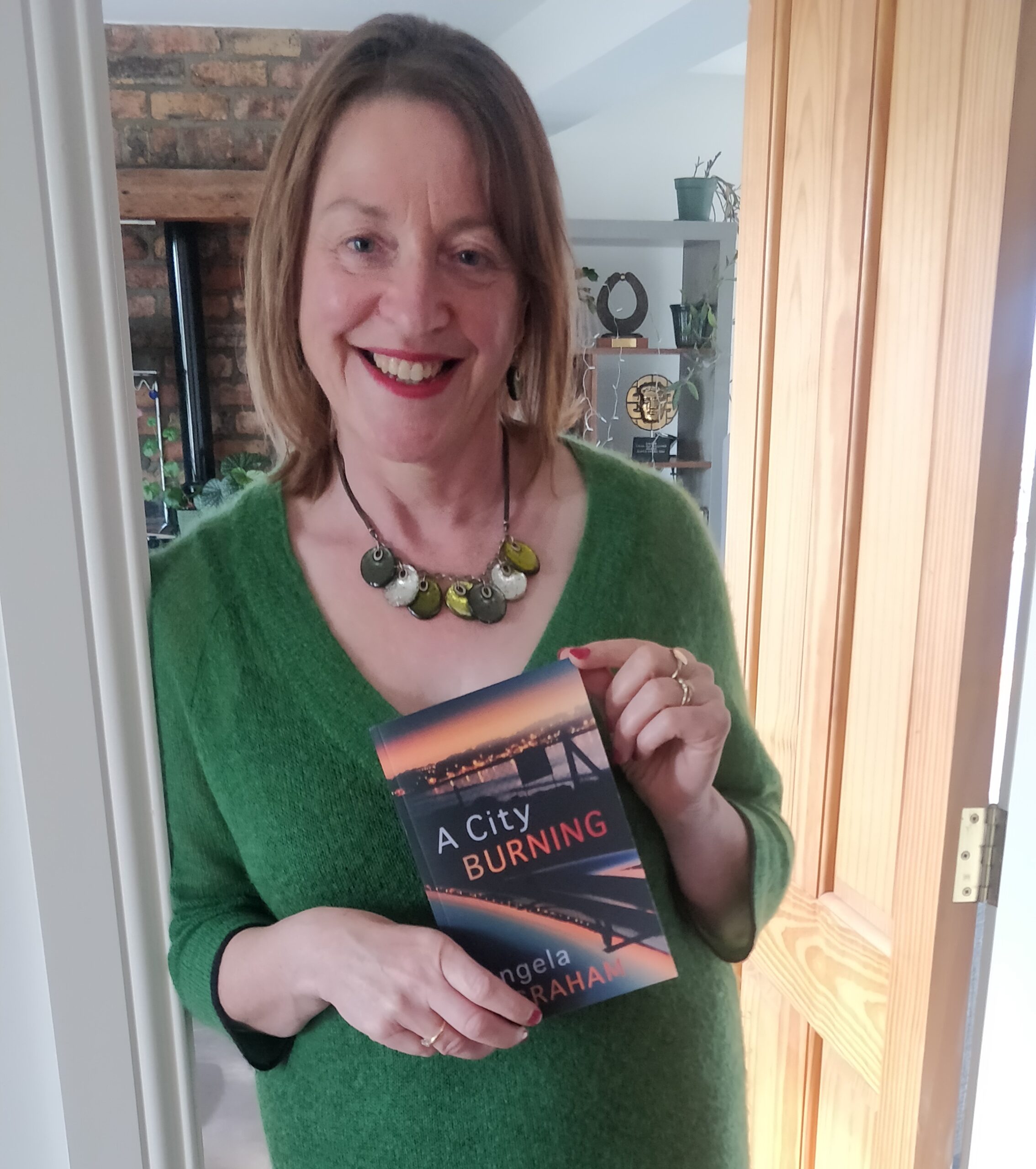

Angela Graham’s assured and compelling debut collection, A City Burning, ranges across Wales, Northern Ireland and Italy. It offers 26 brief stories, most no more than a few pages (one a mere page and a quarter), which turn their forensic flashlight on a moment of change when a character has to make a choice.

In the opening story, ‘The Road’, a filmmaker remembers a scene she has recreated from her childhood, watching though an open doorway as her mother talks to a neighbour. It is summer 1969 and East Belfast, ‘where ninety-six per cent of the inhabitants are Protestant and my family are not among that number’. Their Protestant neighbour has never stopped to speak to them before but now, the city in flames and alive with sirens, she seeks some kind of contact, or reassurance. ‘A child can choose,’ the narrator tells us, and the burning city of this tale gives the collection its vivid title metaphor, an image of roads taken, or not taken, under the pressure of violent change.

Graham is a television producer/director and screenwriter, and her stories have a film-maker’s eye for a framing shot and, particularly, for light effects: sunlight hitting a passageway, stars ‘like sugar spilt across a slate’. She is also a poet and her scriptwriter’s ear for dialogue, in English, Welsh, Ulster Scots and Italian, is combined with a redemptive lyricism. In ‘All Through the Night’, a middle-aged man on a cliff-top at the ‘very edge of Wales’ contemplates the end of his marriage and, mad with desperation, sings into the darkness the words of ‘Ar Hyd y Nos’ finding in their beauty something to hold onto. These are characters who face a moment on the edge and, like the woman finding herself unexpectedly in a familiar cove in ‘Coasteering’, are sometimes shown a way – ‘Breathe. Believe’ – to accept themselves.

The question of what it means to witness – to see or be seen – runs through several of these stories. Often Graham’s characters must learn to see anew. A young priest, caught off balance by the realisation of a fellow-priest’s homo-eroticism in ‘Above It All’, is jolted into compassionate self-knowledge by learning to look at the beatification portrait of a man who loved men. In the troubling ‘Life Task’ set in post-war Italy, the narrator watches a wife unhesitatingly claim her horribly mutilated soldier-husband and resolves: ‘I want to be seen like he was.’ And in ‘Snapshot’ a confrontation between two couples over a minor car incident in Antrim shows one woman how she appears from the outside: ‘Had she looked like that? Stolid and unmoved. Blank.’ Some damage, she realises ‘doesn’t show till later.’ These stories show us what the genre does best: the ‘snapshot’ of a moment which reveals a life or a culture in a moment of transition or realisation, what James Joyce called an ‘epiphany’.

”Most people’s lives are small-scale,”’ says the actor who narrates one story, ‘”That’s what’s so awful when the Bad Thing happens: the life just bursts apart ‘cos it wasn’t meant to contain this much pain.”’ Covid-19 has been a ‘Bad Thing’ which has burst lives apart at every level. Two stories here focus on the small scale to weigh the global damage in the balance. In ‘The Scale’ a care worker in the south Wales Valleys struggles, wearing inadequate PPE, to maintain her professional calm in the face of an old woman’s malicious goading. The old woman’s ‘strike’ against her care workers brings back memories of the 1984 Miners’ Strike and the recognition that, ‘The weak against the weak keeps the strong strong.’ And in ‘Sugared Almonds’ the widow of a bus driver remembers a life warmed by his loving equanimity and lashes out at the lack of protection which left him, along with security guards, shop assistants, construction workers and cabbies, ‘Four times – FOUR times – more likely to die’. Powered by anger at what has been done to ordinary people, these stories are shaped by the recognition that, even at crisis point, we can choose how we respond.

The short story has been having a moment for some time now with powerful but still relatively under-recognised work from writers like Helen Simpson, Carys Davies, Tessa Hadley, Claire Keegan, Chris Power, David Constantine and Mary-Ann Constantine. This vivid, humane and beautifully-controlled collection suggests Angela Graham is another name to watch.

A City Burning is available from Seren Books