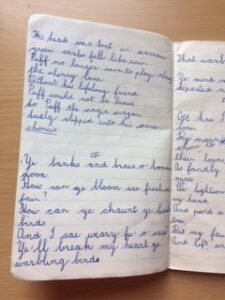

How did I first encounter the poetry of Burns? I wouldn’t have been able to tell you till a few days ago. I came across a small school exercise book, carefully covered in brown paper, on which I’d written the word ‘Songs’ on one cover and ‘Poems’ on the other. I would have been seven years old and the teacher must have written on the blackboard for us to copy down texts in our very best handwriting.

The poems are a mixed bag. The first, I have carefully noted, is by ‘Lord Tennyson’, and I will pass over it because I wasn’t impressed. One of his weaker ones. Didn’t he have better things to do, I wondered. Among the poems was a long one by Thomas Campbell, The Irish Harper. It’s a lament for ‘poor dog Tray’. I know now that Campbell was a Glaswegian (1777 – 1846) who despite a very small poetic output managed to exert much influence on the poetic scene of his day.

Here I’m making a wee aside to recommend Duke Special’s rendition of On Account of My Dog Fido (” oh my dog what have you done? and why have you forsaken me?”). This is a genuinely affecting dog lament from the Francis J. Bigger collection in Belfast Central Library. It’s on A Note Let Go, a marvellous album made with Ulaidh which includes some poem/song work and mines the Bigger collection .

https://www.ceolmusic.ie/products/ulaid-duke-special-a-note-let-go-cd-lp

I’ve blogged previously about other aspects of the album here.

The poems in my school jotter are not the best nor the worst examples of the art but it wasn’t among them that Burns appears. He is in the Songs section. Following on from Puff The Magic Dragon is: Ye banks and braes… (two songs of loss!). There are several Scottish songs in this homemade anthology and a couple in Irish, written conventionally and phonetically. This is how it should be: one language alongside the other.

It was through the song versions of Burns’s poems that I got to know his work. I seem always to have known My luve is like a red red rose… And a Scottish friend singing For a’ that blew me away. Simply delivered, with conviction, the refrain convinces us that the truth is simple: it’s not outward show or possessions that count because every individual is inherently worthy by virtue of being human. The poem, or song, makes its confident assertion that, ultimately, right values will prevail.

For myself, as a poet, to reimagine Rabbie means letting his work inspire me to reimagine myself, my society and my role in that society. As a writer, what am I for? What is my purpose? I won’t ignore the lesson Burns offers that poetry as singable lyric extends the poem’s reach and expands it beyond poet and solitary reader.

https://linenhall.com/events/rabbie-reimagined-gibson-burns-and-belfast/

I’ve chosen another poem that is also a song, John Anderson, my jo, John.

This is a poignant yet celebratory account of a long relationship. And a lovely song.

Angela Graham is a film maker, writer and poet. Her short story collection A City Burning (Seren Books) was longlisted for the Edge Hill Short Story Prize 2021. Her poetry is widely published.