‘A dream unquestioned is a letter unopened’. Apparently. Do you agree?

Twenty years ago I was in the grip of prolonged and serious physical pain due to a then-undiagnosed condition. I couldn’t work as normal. I spent long periods confined to the house. Someone was very unkind to me and, as a way of acknowledging his fault without having to say it aloud, he handed me a book, saying I might find it of interest. I had plenty of time to read it thoroughly, footnotes and all and, in one of those, discovered a reference to a book that came to mind forcefully this morning.

I woke from a dream so vivid and engaging that I was able to write down the dialogue between the figures in it and to describe their outward and inward dispositions, partly because I had ‘been’ them all, inhabiting the action from their perspectives. This is not possible in waking life. At least not with the immediate and assured access a dream affords.

This morning’s scenes, I realised, in which I was both multiply participant and also the observer, opened up for me a way to go deeper into a character in the novel I’m writing.

I wonder how common it is for writers to take advantage of what dreams offer?

The dream seemed to open out before me (but also to allow me to experience from within) a certain character, from a viewpoint I hadn’t considered, even down to his physical appearance and inner attitudes. For a writer, this can’t but be astonishing. I’m in charge, aren’t I? So why was it as though someone took the script, tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Look at it this way.”?

But before I write more about ‘this morning’s’ book I want to mention another that may have prepared the ground in me.

About thirty years ago a book arrived across my desk from a publisher hoping it might be the seed of a tv series. It didn’t go that way but “Hypnagogia, the Unique State of Consciousness Between Wakefulness and Sleep” by Andreas Mavromatis opened my eyes to the potential significance of that state on either side of the threshold of sleep.

Creative people do make use of this liminal stage. Edison, for instance, would hold some metal balls in one hand and let himself drift off. Waking when his grip relaxed and the balls clattered to the floor, he would immediately note down whatever had come to him.

A famous illustration by R.W. Buss (David Perdue’s Charles Dickens Page) showing Charles Dickens relaxed in an easy chair while his creations swarm around him, may depict the sleeping/waking state of creativity.

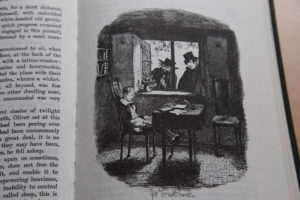

And in ‘Oliver Twist’, chapter 34 contains a description (illustrated by Cruikshank) of another type of liminal state in which Oliver is caught in ‘the kind of sleep that… while it holds the body prisoner, does not free the mind from a sense of things about it…’

However, the experience of the un-prepared-for dream, which rises without one’s apparent agency yet seems to have particular import, never loses its impact.

The book that gave me some ways to take better advantage of dreams is Dreams and Spiritual Growth. Unlike those one-size-fits-all dream dictionaries, this book offers simple, gentle, effective ways of considering a dream. The book’s roots are in the Judeo-Christian tradition but are suitable for anyone who can accept that dreams ‘come from a source other than one’s own consciousness’. I’d say the techniques are valid even for those who don’t accept this.

We’ve all had dreams which make a big impression on us, which seem to claim attention despite components which are illogical or bizarre or far from what we’d allow ourselves to endorse in waking life. The book’s thesis is that a dream does not so much provide information as pose a question. Pinpointing the question is often, in itself, very elucidating. It gives a focus. We can begin to work.

A dream, the authors maintain, is a gift, not only for the individual but for the community and also an invitation towards relationship rather than something alienating.

Techniques are offered to help one deepen understanding of symbols and images in a dream in order to explore the associations within a dream which are unique to oneself, though these always exist within cultural matrices.

Dreamwork has become part of my life, as an almost everyday habit. I have become used to acknowledging dreams when I wake. I spend a moment considering them. If there is anything particularly striking I make a note and can choose to devote more time to opening the dream up.

It is best to read the book as a whole as taking parts out of context doesn’t do it justice. So I refer to this helpful technique recommended there only as an illustration of its approach: TTAQ –

give the dream a Title

establish its Theme

acknowledge the Affect (how did one feel at various stages of the dream)

consider what Question the dream may be posing.

There is no sense of coercion. One is not obliged to accept one’s own responses. Freedom of reaction is paramount. However, I’ve found this procedure to be enriching and always positive.

Being in control and relaxing control seem to be significant in this whole arena. Imagination flourishes when we are open but not assailable – it’s certainly not about making oneself vulnerable to damaging forces.

Some of the dreams I’ve worked with have become significant sources of insight, consolation and challenge. And I think the practice may even act as a workout for my imagination! For a writer, that’s no bad thing.