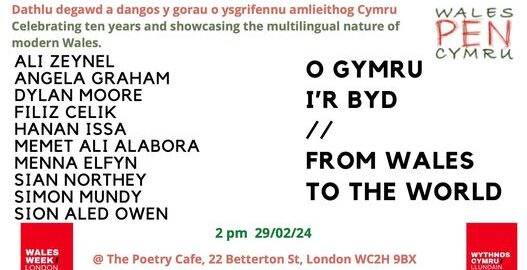

During Wales in London Week, around St David’s Day, there’s a celebration of the significant contribution to London of Welsh culture. On February 29th WalesPENCymru held a poetry reading and music event at The Poetry Society’s Poetry Cafe to mark the organisation’s thenth anniversary. The theme was ‘Wales as a Multilingual Country’.

The Wales branch of PEN is one of the largest in terms of membership. It is affiliated to PEN International.

PEN promotes literature and defends freedom of expression. It campaigns on behalf of writers around the world who are persecuted, imprisoned, harassed and attacked for what they have written. It has committees representing writers in prison, translation and linguistic rights, women writers and a peace committee.

A glance at WalesPENCymru’s website shows the range of events and campaigns that run throughout the year http://walespencymru.org/ They are all designed to support the freedom to speak of writers and journalists worldwide and also in Wales and the UK.

I was invited to read my poem, ‘Colony’ which is about what happens to language in the process of colonisation and I wrote a new poem for the event, ‘Wales/Cymru’.

At the London event we listened to the National Poet of Wales, Hanan Issa (below). And to Wales PEN Cymru’s president, the renowned Welsh poet, Menna Elfyn.

The Turkish writer Mehmet Ali Alabora spoke about living in Wales and the importance of the Welsh language.

The Kurdish musician, Ali Zeynel (below) played and sang in his minority language and then gave us the Welsh folksong, ‘Dacw ‘nghariad i lawr yn y berllan’.

photos and video by Dominic Williams of https://write4word.org/write4word

Watch the event on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HsioNQ3TddM

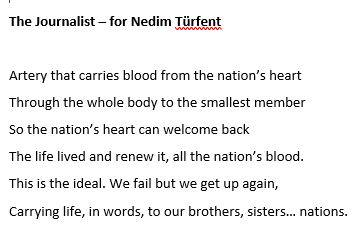

In my collection, Sanctuary https://www.serenbooks.com/book/sanctuary-there-must-be-somewhere/ I have a poem written for Letter With Wings, an Irish PEN campaign for the release of the unjustly imprisoned jounalist, Nedim Turfent. Thankfully he was released in Novemeber 2022, after 6 years in prison.