All posts by angela

A-WAITIN ON THA WHUSSLE

36TH (ULSTER) DIVISION, 7.21 a.m., 1st July 1916

A’m liein here this brave while,

yin o Genèral Nugent’s men,

oot in Nae-man’s Lan gye an earlie

that bit neardèr tae thaim Huns,

tae be readie, an mair nor readie,

fur whan tha whussle wheeps.

A’m liein here this lang while,

face-doon in tha glar,

tha barrage up aheid.

Barrage,

a saft, saft wurd

fur a wile heavy thïng.

Barrage, Barrage – lik whut ye’d say

tae peacify an ailin baist,

straikin its sheeglin hide,

“Barrage, barrage, oul sinn,

yer pain’ll soon be bae ye.”

Barrage! Barrage! Barrage!

a wrathsome nieve, blargein,,

duntèrin, poondin…

… till tha delf leps frae tha boord

an doon it dings agane

Agane, agane he’d dae it,

a man tae murdèr

onie bit o peace.

A’d lie, face doon, oot o his road,

ma hauns tae ma lugs,

keepin him oot o ma heid.

Ma faither…

Aa tha wrathsome faithers o tha worl

is here theday,

blattèrin thair weans

in yin great stramash.

we ir sae smaa unnèr this sky o shells,

tha grun aneath iz swallaed up bae soon

an we its spu’ins! Thon scraich

wull split ma heid!

Struck deef…!

Nae soon? Tha

guns hae

stapt.

Yin mïnit fur tae tak a braithe …

Yin mïnit fur tae see, sae clear,

sae clear, thon lang-deid man,

but, sae clear jest noo,

a luk o pain

flictèrin owre his face…

Yin mïnit mair

an A’ll be on ma feet

fur God an Ulstèr an tha Croon…

Ma Faither God, ye didnae spare yer sinn.

Inunnèr hemmer blows Ye lee’d him

Yit an wi aa he sayed, “Intae Yer hans…”

Ma sperrit… can A trust Ye wi it?

An wi ma faither’s…?

… fur tha sake o his yin nekked luk o sorra,

eneuch tae mak ma hairt gae oot tae him

an thon’s tha whussle

an tha wurd

that haes me up

an forrit

intae Yer hauns…

On the first morning of the First Battle of the Somme (1st July 1916), General Nugent sent Armagh Volunteers into no-man’s-land before zero hour. They had to lie and wait till the whistle blew for the general advance at 7.30am, the idea being that they would be that bit closer to their objective (the Hun). The first of them were sent out at 7.10am and then three further groups of Nugent’s Ulstermen at five-minute intervals. They had to lie under the ‘curtain’ of British shell bombardments passing above them. This must have been a horrifying experience.

This poem appeared in ‘Yarns’, 2021, an anthology of Ulster-Scots writing published by the Ulster-Scots Community Network. My grandfather was from Newtownstewart in County Tyrone, so the poem is not based on his experience. He was in the 36th (Ulster) Division which also took part in this battle. I wrote this poem in Ulster-Scots because he and so many of the men would have spoken like this. A tiny glossary: Glar sticky mud; Sheeglin trembling; Nieve fist.

Burns and the modern Ulster-Scots writer – Steve Dornan

A writer writes. But insights about cultural context are important and, for the writer, intriguing. We plash about in the stream of words. It’s good to lift the head and see what kind of a stream – or burn – it is.

Robert Burns and Modern Ulster-Scots Poetry Steve Dornan, in this enlightening essay for the Burns Chronicle, {Burns Chronicle 132.2 (2023): 204–215, published by Edinburgh University}, explores “how Burns’s increased visibility in Ulster is replicated in the work of modern poets who use Ulster-Scots in their work.”

Burns has been increasingly foregrounded in recent years, as Dornan notes, “in official presentations of Ulster-Scots by the Ulster-Scots Agency and other public bodies. High-profile Burns Night concerts are now a staple and TV programmes have been commissioned to mark the occasion. Burns’s image also features prominently on the Ulster-Scots Agency websites and promotional materials. Has this increased visibility led to writers re-engaging with Burns, or can modern Ulster-Scots poetry be viewed as definitively ‘post-Burns’?”

This making Burns visible, as it were, (actually on the streets in the presence of display banners in Belfast city centre, for instance) is perhaps a cyclical phenomenon. Prof. Wesley Hutchinson, in his article ‘Constructing An Ulster-Scots Burns’ traces the ways in which Burns’s work and ‘heritage’, was ‘curated’, from the mid-nineteenth century to just after the First World War, to serve the interests of one or other social or political group.

Dornan himself is central in the current florescence of Ulster-Scots writing, being the author of the genre-busting poem, Tha Jaa Banes. As he says himself, “The title poem, ‘Tha Jaa Banes’, is a semi-ironic supernatural Ulster-Scots romp which alludes at several points to the unquestionable masterpiece of the genre, Burns’s ‘Tam o’ Shanter’. In terms of form, voice, language and theme, echoes of and dialogues with Burns might be apparent to readers familiar with the work of the Ayrshire Bard.”

Dornan traces how verse forms typical of Burns’s work appear, or do not appear, in modern Ulster-Scots writing. And he examines Seamus Heaney’s acknowledgement of the influence of Burns and Heaney’s own use of the vernacular. Dornan’s own work engages directly with Burns’s, perhaps, he suggests, because he lives in Scotland and studied at a Scottish university.

He assesses the influence of Burns on the work of of several contemporary Ulster-Scots writers and how it compares to the generation of writers who came to prominence in the 1990s such as James Fenton and Philip Robinson. Their consciousness of Burns, he believes, ” tends to stop short of the direct engagement with his work that was evident in previous generations of Ulster-Scots writers.”

He invites the writers, Alan Millar, Robert Campbell and Anne McMaster to consider Burns’s influence on their work. Their responses are, it seems to me, invaluable insights into a working process that is happening right here and now in Northern Ireland, a place which is not, to state the obvious, Scotland. It shouldn’t be surprising that Burns registers in ways that are unlike, and like,his impact in Scotland.

Robert Campbell refers, Dornan writes, to “childhood memories of looking at the illustrations in his grand-father’s nineteenth century ‘Edina’ edition of Burns’s poems, a volume which he subsequently inherited. This is a nice symbol for the sort of organic folk culture that traditionally exists around Robert Burns in Ulster. Campbell talks about Burns’s role in convincing him that Ulster-Scots is a valid medium for writing. He says: ‘It was the validation of language that was most important. He was an icon of literature but we were stupid for using the same words.’

Alan Millar, according to Dornan’s interview with him, recognises “the indirect influence of Burns. Millar is an enthusiast of writers from the Ulster-Scots tradition, who are much less globally recognised than the Scots tradition’s iconic poster boy. He says, ‘I approached Burns through the likes of (Samuel) Thomson and (James) Orr, the Ulster-Scots tradition. So his influence on me has an indirect element.’ The influence of these Ulster-Scots writers, sometimes collectively known as ‘The Weaver Poets’, or ‘The Rhyming Weavers’, is evident in several of his poems that use traditional stanza forms such as standard Habbie. In 2020 his poem ‘Wee Weaver Birdie’, which won the Scots Language Association’s ‘Tassie’ prize for best poem in 2021, alludes to this tradition. This poem uses the image of the wee weaver birdie as a metaphor for the Ulster-Scots tradition and its decline.”

Anne McMaster “also speaks of an indirect connection to Burns. In a statement that it is difficult to imagine a Scottish writer producing, she says: ‘I came late to reading Burns, and understood him as a pre-Romantic poet who had a real affinity with nature and the human condition.’ Anne McMaster appreciates the emotional impact of Burns’s language. She says: ‘It’s totally different from English – there’s a visceral response in reading his work (and in doing my own creative work in Ulster-Scots) that I don’t / can’t feel when writing in English.’ (I agree.)

Steve Dornan interviewed me. Angela Graham, he writes, “feels influenced by some of Burns’s aesthetic choices and in particular his propensity for combining contrasting elements in his work: ‘I’d say I am influenced by those poems of his which appear simple in sentiment and rhyme but which carry a strong current of feeling; also his humorous poems. I don’t seem to come across much contemporary poetry which is deliberately light, amusing and double-layered, entertaining while conveying something solid.’

“This inclination,” Dornan says, “towards contradiction and paradox is something that has been mooted in critical writing on Scottish poetry from as far back as G. Gregory Smith’s famous characterisation of Scottish poetry as embodying a ‘zigzag of contradictions’. This suggests that Burns, for writers of Ulster-Scots, can represent wider aesthetic possibilities that go beyond the linguistic.”

Steve Dornan concludes: “A modern poet from Ulster, in contrast to a Scottish counterpart, is likely to have experienced a different level of exposure to Burns in educational settings and popular culture. This perhaps means that there is less necessity for writers of Ulster-Scots to engage with Burns, whether in emulation, or ostentatious bouts of bardoclasm. Writers from Ulster, therefore, have the freedom to engage with and re-discover Burns on their own terms.

“On the other hand, of course, good poetry cannot exist in a vacuum and is often in dialogue with tradition. Whether the traditional forms used by Burns are present or not, Burns can act as a useful avatar for writers who use Ulster-Scots in their work: the confident non-standard voice, the unabashed celebration of the marginal, the subtle, elusive artistry of his personae and the thrawn recalcitrance of his language and social commentary are all of value to any of us.”

As a writer in Ulster-Scots I’ve found Steve Dornan’s questions thought-provoking. My initial encounter with Burns’s work was in my childhood through songs, whose words we copied from the blackboard. So the words reached me as verse and as music. They were, therefore, ‘mine’ from my earliest years. Over the years I’ve enjoyed traditional Scots verse forms, often encountered through Burns and these have become mine also and form part of my writing repertoire. I find the technical challenges they set and their vernacular demand for authenticity and avoidance of pretension invigorating.

A very useful insight from Steve Dornan onto an aspect of the current Ulster-Scots writing scene.

And to meet some Ulster-Scots writers in person –

AYONT THE HAMELY TONGUE

The Linen Hall 17 Donegall Square North, Belfast, United KingdomThis year, The Linen Hall is proud to mark the Ulster-Scots Language Week with an evocative poetry reading event. Six distinguished poets—Robert Campbell, Angeline King, Ronnie McIlhatton, Anne McMaster, Alan Millar, and Morna Sullivan—are coming together to take us on a journey of words and emotions. Join us for a celebration of the Ulster-Scots heritage and talent.

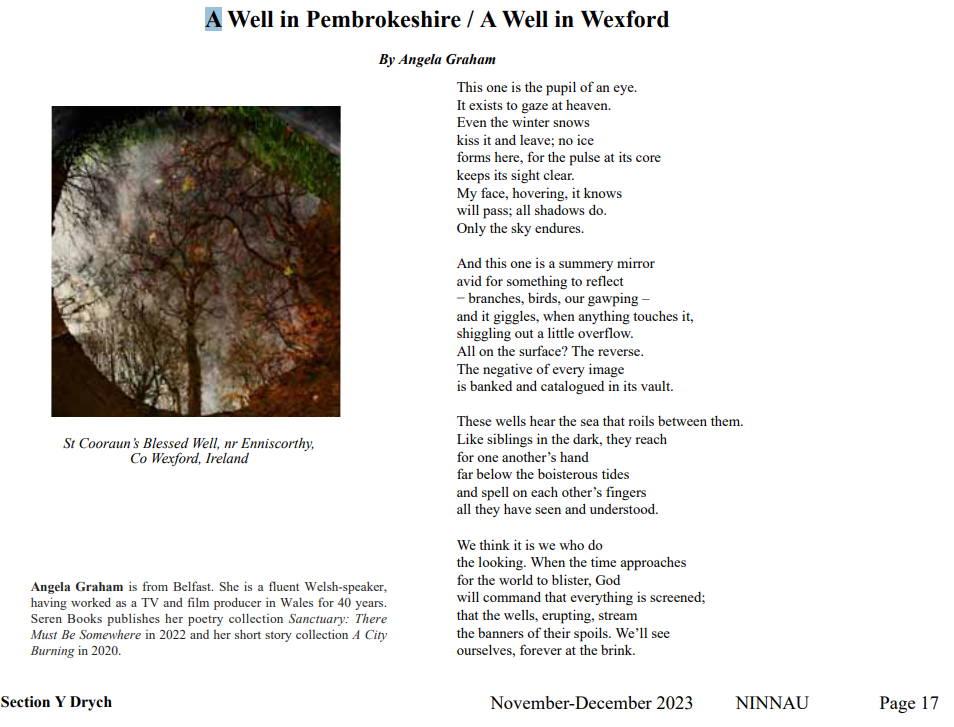

Poem in NINNAU, USA’s magazine of Wales

NI Screen: new archive of contemporary Ulster-Scots writing

Featuring some of the best contemporary Ulster-Scots poets, including Charlie Gillen, Anne McMaster, Angeline King, Angela Graham and Liam Logan, Negative Waves and Sub-Culture Productions have curated a large collection of Ulster-Scots audio and video recordings highlighting and preserving their important work. The digital project has been made with support from Northern Ireland Screen’s Ulster-Scots Broadcast Fund.

The link above gives access to video and audio recordings.

Ulster-Scots Poets bloom at the Sunflower

On the 5th August a great time was had by all at a showcase of contemporary Ulster-Scots poetry organised by poets themselves. This was the first time that some of us, who have been in regular contact in the last few years, had met in person. The event was characterised by a very supportive atmosphere which really helped everyone shine. For one poet, it was the first time he had read in public and he did so with aplomb.

Left to right below, Angeline King, Ronnie McIlhatton , Steve Dornan, Al Millar, me, Robert Campbell, Rob Morrow, Anne McMaster and Liam Logan.

‘Colony’ Poem in Poetry Wales vol 59 Summer

COLONY

Your words in my mouth

are bitter

a double dispossession:

of the land itself,

of its relationship with me

- a double supplantation.

My words in your mouth

are strange

a double reiving:

of my tongue itself,

of its cadences and music

- a double apprehension.

This is the first stanza of my poem in the current issue of Poetry Wales summer 2023. ‘Colony’ goes on to describe how the language of the coloniser enters the colonised, establishing a kind of internal territory, invisible but powerful.

The poem then envisages the ‘journey’ of the language of a colonised people into the coloniser, where it affects the coloniser’s inner life in ways unexpected in the act of colonisation.

These processes are colonisations at the most intimate levels. What hope is there for a just and mutually positive outcome?

Please consider reading the whole poem in Poetry Wales

Review of Sanctuary.. in Poetry Wales

Elizabeth Kemball reviews ‘Sanctuary: There Must Be Somewhere’ (Seren Books) in ‘Poetry Wales’ Summer 2023

Extract – ‘Angela Graham’s timely collection … unflinchingly addresses challenging issues of the current climate, from the pandemic to war in the Ukraine with a tender voice that is respectful of the subject matter… Through Graham’s collaboration with the five other poets who feature in this collection, the additional voices add to the exploration of what sanctuary is to each of us and how much this adapts and transforms in the face of upheaval and global turmoil… this collaborative approach only strengthens the message and quality of the work… In the poem ‘Since The Evacuations from Kabul’ we are asked the question that is essential to these poems

Is there a scathing truth we have to face,

that outside every sanctuary there’s a hell

where howling crowds who crave the sacred space

clamour to join the saved?

This stanza deftly cuts to the root of sanctuary: if it is a place then it is also a privilege, do which of us are allowed in?’

Writing of the inclusion in the book of a poem by each of Mahyar, Csilla Toldy, Viviana Fiorentino, Phil Cope and Glen Wilson:

‘This collaborative approach only strengthens the message and quality of the work within, as Graham explains in the foreword ‘TO eb permitted to engage at increasingly deepr levels challenges poth parties… something new emerges… and we go ahead in the pursuit of the true, the real, the poetically beautiful’ – this too is true of the idea of sanctuary, which becomes more rounded with the inclusion of multiple voices…

‘Angela Graham ends … with a poem about home. ‘Home’ is a hopeful piece that emphasises that at the heart of sanctuary is humanity: ‘We are a home for one another. And this holds true for everyone’. These final lines are perhaps the most poignant in the whole collection and remind us… that in turbulence of mundanity, whether human or animal, we each must carve a space to fit ourselves, around each other.’

https://www.serenbooks.com/product/sanctuary-there-must-be-somewhere-paperback/

Poetry & Current Affairs

The pace of current events worldwide seems to have accelerated. That is probably not the case, merely an impression, since what qualifies as an event must depend on the point of view from which circumstances are being judged. Undoubtedly , the upheavals in Russia and their impact on other countries are major events. Their impetus shifts bewilderingly fast. How can poetry keep up?

I felt compelled to write a poem in immediate reaction to news that Yevgeny Prigohzin had launched a march on Moscow. I had scarcely finished it when the headline was that he had called it off.

I wrote this article about my experience of crafting a poem about events that were changing with extraordinary speed. It was published by the Institute of Welsh Affairs. It includes my poem, Prighozin’s Galley Slaves.

Zoe Brigley, co-editor of Poetry Wales, edited the first draft of this article.

Peterloo Massacre, print published by Richard Carlile, 1 Oct 1819 (Manchester Archives, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Highly Commended poem in Frances Browne Poetry Competition

It is an honour to have my poem Tha Watch Hoose Atap Tha Cliff Highly Commended in the Ulster-Scots category of the Frances Browne Poetry Competition.

The Frances Browne Festival is an annual celebration of the 3 tongues of the locality: Irish, English and Ulster-Scots. The Festival is enabling a welcome surfacing of ability and engagement in a very constructive spirit.

https://www.francesbrowneliteraryfestival.com/poetry-competition